Chasing the Ghosts of Choice

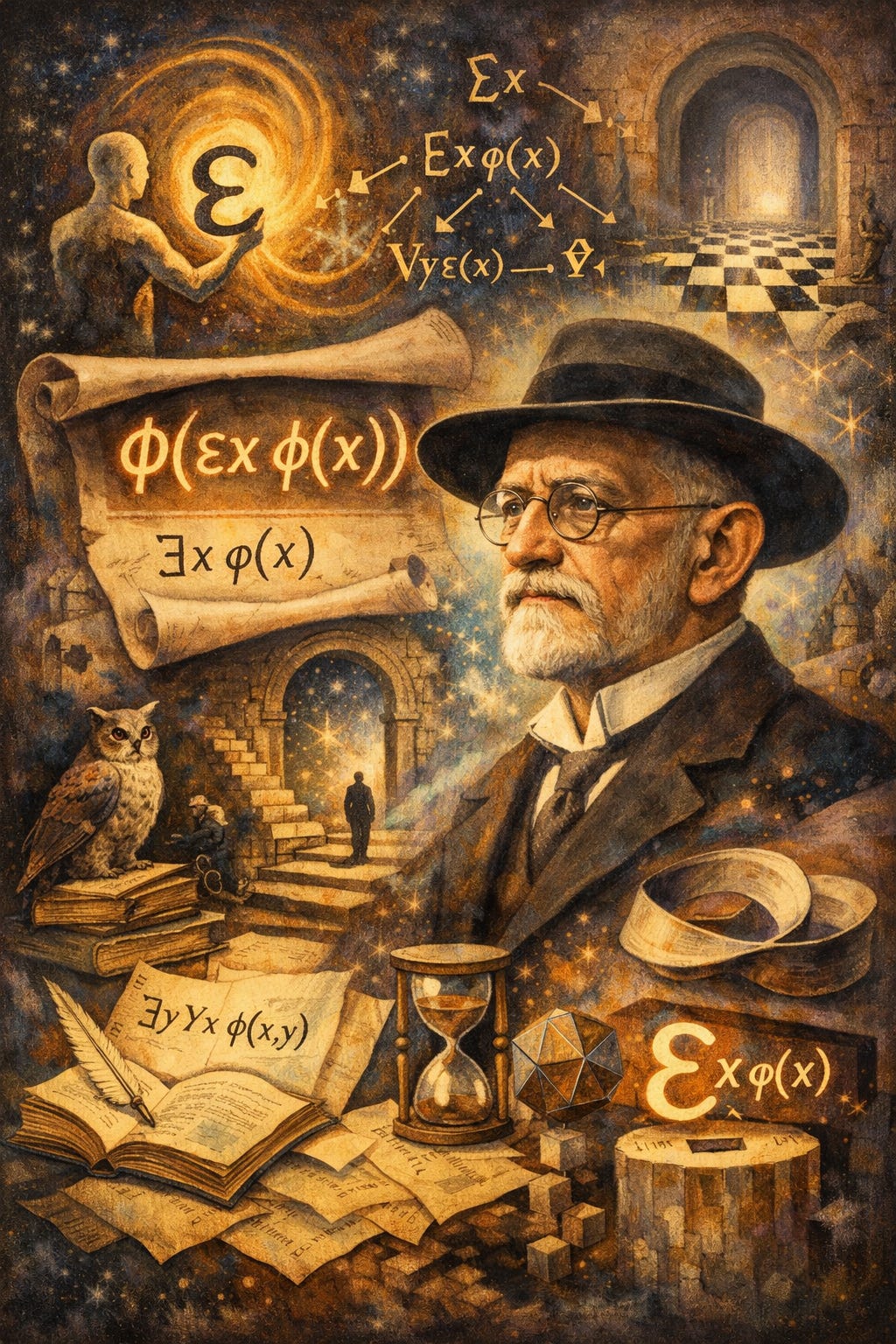

A Journey around Epsilon Calculus and the Architecture of Logic

Ghosts in the Machine

As many of you may have noticed, I’ve always been fascinated by the parts of mathematics we rarely see: the hidden scaffolding beneath the theorems, the silent mechanisms that make logic tick.

When we read proofs in textbooks, we generally think we’re engaging with numbers, functions, and sets; but in truth, we’re often interacting with placeholders, choices that exist only in the language of the proof.

In the 1920s, David Hilbert confronted a universe of trembling foundations. Mathematics had survived centuries of exploration, but cracks were appearing everywhere.

Things like Russell’s paradox had shaken the set-theoretic bedrock. Intuitionists were protesting the law of the excluded middle. And Hilbert, ever the strategist, asked a critical question, both audacious and subtle:

could we formalize mathematics in a way that made every proof finitary, concrete, and yet completely reliable?

His answer introduced a concept that is at once deceptively simple and profoundly transformative: the epsilon operator, a ghostly placeholder for existence itself.

It’s a symbol, a term, a choice, and yet it is nowhere.

This essay will take you on a journey through this idea; more precisely, I will show it through its origins, its technical brilliance, its philosophical implications, and its surprisingly modern applications in logic, language, and computation.

The Problem of Existence in Proofs

Mathematics, for most of us, begins innocently enough with numbers.

We start to count apples, we play by measuring distances, then calculate things like interest rates for our mortgage, and slowly, we build comfort with the idea that symbols on a page can correspond to concrete things in the world.

But very quickly, numbers alone are not enough. Sets appear: collections of objects that obey certain rules, that can be manipulated, compared, combined.

And then, inevitably, the theorems begin; statements of truth that seem to emerge almost magically from the interaction of definitions and axioms.

But underneath all of this familiar structure lies a far more subtle and delicate dance, one that often goes unnoticed by students and practitioners alike.

It is the dance of existence and reference, of objects that we reason about but never actually see.

How do we talk about something without ever having it in front of us?

How do we manipulate the invisible, the hypothetical, the possible?

Consider a deceptively simple example: “There exists a number x such that x² = 4”. At first glance, there seems nothing controversial here. x could be 2, or it could be -2.

That’s it. Problem solved. But suppose we want to work with this statement formally, in a proof that will later be checked by other mathematicians, or even, eventually, by a machine.

Suddenly, the question becomes: how do we refer to some x that satisfies this property without arbitrarily picking 2 or -2? How do we keep the reasoning rigorous, consistent, and general, while still talking about an object that we haven’t concretely chosen?

Before the 1920s, mathematicians were often content to rely on existence implicitly. You could prove that something existed, and the proof itself did not require you to construct or exhibit the object.

This approach worked remarkably well in practice.

Mathematicians could navigate the infinite landscapes of numbers, functions, and sets with implicit existential reasoning, confident that their logic would hold.

But as the field of mathematics matured and the drive for formal rigor intensified, these implicit assumptions became a point of tension.

A New Way of Thinking

Philosophers and mathematicians such as Brouwer, Hilbert, and the intuitionists began asking difficult questions:

if a proof relies on an object whose existence is asserted but never demonstrated, can we truly trust the proof?

Is it enough to know that something exists in principle, or must we be able to construct it?

The stakes were high, and the problem was more than philosophical: it threatened the foundations of mathematics itself.

It was in this context that David Hilbert, a towering figure of 20th-century mathematics, proposed a radical idea. What if existence itself could be treated as a manipulable object within the language of logic?

What if we could create a symbol, a term, that stands in for “some object that exists” without committing to any particular choice?

Hilbert’s answer was the introduction of the epsilon operator, denoted ε.

Formally, if A(x) is some property, then εxA is a term that represents some x satisfying A, if one exists. The epsilon operator does not care which x it picks; it does not resolve the ambiguity inherent in the existential statement.

It is, in a sense, a ghostly placeholder, a symbol that carries the weight of existence without ever revealing the identity of the object it refers to.

At first glance, this may appear to be nothing more than a convenient shorthand. But in reality, it represents a profound shift in how proofs can operate.

With epsilon terms, Hilbert showed that existential quantifiers (long considered fundamental) could be replaced entirely with symbolic terms. Instead of writing “there exists x such that…”, we write “let εxA be such that…”, and the proof proceeds with this term as a stand-in.

The brilliance lies not only in elegance but also in control and rigor. By transforming existential statements into concrete symbolic terms, Hilbert provided a way to manipulate existence directly in a proof.

We no longer rely on vague assertions; instead, we can reason about the placeholders themselves, apply logical rules, and eventually reduce proofs to forms that are fully verifiable using finite, mechanical methods.

In other words, the epsilon operator is more than just notation. It is a bridge between the abstract and the concrete, between potential and actual, between the philosophical question of “does something exist?” and the practical task of reasoning about it.

It allows mathematicians to engage with the infinite, the hypothetical, and the unseen, while keeping their feet firmly planted on finitary, verifiable ground.

This approach would later prove essential for Hilbert’s broader program: the attempt to formalize all of mathematics in a way that guaranteed its consistency and completeness: a dream that, though ultimately limited by Gödel’s incompleteness theorems, profoundly shaped the course of logic and proof theory.

The epsilon operator was not just a technical device; it was a conceptual breakthrough, a tool that transformed how mathematicians think about existence, choice, and the architecture of reasoning itself.

By introducing a manipulable symbol for existence, Hilbert turned an abstract philosophical idea into a concrete, formalizable object.

He gave mathematicians a way to handle the invisible, to reason rigorously about objects that might never be constructed, and to navigate the infinite with finite steps.

It is, in a sense, an act of intellectual alchemy: turning the ghostly “there exists” into something tangible, something one can write down, compute with, and eventually eliminate from a proof if necessary, leaving only the skeleton of logic behind.

Introducing the Epsilon Operator

Let’s now dive into the formal concept of the epsilon operator, which at first glance seems almost deceptively simple. Suppose we have a logical statement, A(x), involving a variable x. Then we define the epsilon term εxA(x) as:

This notation is elegant in its economy. It doesn’t ask us to choose a specific x, it doesn’t force us to verify each candidate individually.

Instead, εxA(x) acts as a stand-in, a symbolic placeholder; a ghost that represents the existence of an x satisfying A, without ever committing to which x it is.

Hilbert gave this operator its formal backbone through what he called the transfinite axiom:

In words: if there exists some x for which A(x) is true, then substituting εxA for x preserves the truth of A.

The epsilon term, in other words, is a logical guarantee of existence, captured symbolically.

It is both a choice and a placeholder, a ghost in the machinery of proof, silently ensuring that the existential claims we make have formal footing, even if we never identify the object itself.

The elegance of ε-terms becomes even clearer when we consider their versatility. Every existential quantifier, which once stood as a primitive and seemingly immutable part of logic, can be rewritten in terms of ε.

For a statement ∃xA(x), the corresponding epsilon expression is simply:

This is very profound. The epsilon term internalizes existence.

Rather than saying “there exists x” as an abstract, generic claim, it converts it into a term that can be manipulated algebraically and logically, treated as a concrete symbol in the syntax of a proof.

But the power of ε-terms doesn’t stop with existentials. Universal quantifiers, ∀xA(x), can also be expressed entirely in epsilon terms, using the familiar logical equivalence with negation:

Suddenly, the landscape of first-order logic transforms.

Quantifiers, which had long been treated as fundamental operators, can now be replaced with terms that represent choice.

Existence, once abstract, becomes something tangible; something that can be written down, referenced, and substituted, without ever specifying a concrete element.

To make this more concrete, consider a simple example. Let A(x) be “x² = 4.” Then εxA(x) represents some x such that x² = 4.

We don’t have to choose 2 or -2; the epsilon term carries the existential weight itself. If we then consider ∀x(x² ≥ 0), we can rewrite it using epsilon notation as:

Even though this looks more complicated than the original statement, it is in fact a powerful move toward formalization: every quantifier can be expressed in terms of symbolic choices, enabling systematic manipulation of proofs.

This isn’t just symbolic sleight-of-hand. The real power of ε-terms is revealed in proof transformation and finitary justification.

By turning existential and universal claims into manipulable symbols, Hilbert opened the door to eliminating quantifiers entirely, leaving behind a skeleton of logic that can, in principle, be verified using finite, mechanical reasoning.

The ghosts (the ε-terms) can be tracked, substituted, and eventually removed, leaving only the solid bones of the argument.

In effect, Hilbert’s epsilon calculus allows mathematicians to reason about existence without being forced to exhibit it.

It bridges the gap between the philosophical intuition that something exists and the formal rigor required to manipulate that existence symbolically.

The epsilon term does not merely represent a choice; it is a logical tool that embodies the very act of choosing, in a way that is compatible with formal, finitary reasoning.

By recasting quantifiers as terms, Hilbert’s approach achieves a rare combination: it preserves the conceptual intuition of existence, while providing a mechanical and symbolic framework capable of grounding proofs in concrete, checkable steps.

It is this synthesis (between abstraction and manipulability, between the ghostly existence of an object and the rigor of symbolic logic) that makes the epsilon operator one of the most elegant and far-reaching inventions in 20th-century mathematics.

In the grander scheme of Hilbert’s program, epsilon terms were not an isolated curiosity.

They were a step toward a broader dream: a fully formalized mathematics where the infinite could be tamed, where proofs could be reduced to finite manipulations, and where every claim of existence could be represented, reasoned about, and mechanically verified.

It is a vision where the abstract becomes concrete, the potential becomes manipulable, and the ghostly becomes something we can write, substitute, and ultimately understand.

Hilbert’s First and Second Epsilon Theorems

To understand the true power of epsilon terms, we need to explore the epsilon theorems.

These results show how ideal elements (terms that stand in for existence) can be removed from proofs under certain conditions, without losing validity.

The First Epsilon Theorem states roughly that: if a formula involving no epsilon terms is derivable from a set of axioms in the epsilon calculus, then it is derivable in standard quantifier-free logic.

In other words, the “ghosts” are eliminable.

The Second Epsilon Theorem generalizes this to full predicate logic: any theorem without epsilon terms that is provable with epsilon terms can also be proven without them. This is not merely technical; it is profound.

It shows that the ideal elements introduced by Hilbert are tools, not crutches. They can guide the proof, simplify reasoning, and then vanish, leaving behind only the concrete content.

These theorems provide a deep insight into the nature of logic: existence can be represented, manipulated, and yet safely removed.

Hilbert had found a method to make the abstract tangible, and then, if desired, invisible again.

Epsilon Calculus and Herbrand’s Theorem

The epsilon calculus doesn’t exist in a vacuum. One of its most remarkable applications is in Herbrand’s theorem, a cornerstone of proof theory.

Herbrand’s theorem bridges two worlds: the abstract derivability of formulas and explicit combinatorial constructions.

It asserts that if an existential statement is provable, then a finite disjunction of concrete instances (the Herbrand disjunction) is tautologically true.

Epsilon terms provide a structured way to construct these disjunctions. By replacing quantifiers with choice terms, one can systematically generate the instances needed for a Herbrand disjunction.

The length of the disjunction depends on quantificational complexity, not on the size of the proof itself. Logic, in this sense, has an internal rhythm: a hidden efficiency that the epsilon operator makes visible.

It’s a rare moment in mathematics when abstraction meets combinatorial clarity.

Epsilon terms are not just symbolic: they are a bridge between infinite reasoning and finite, checkable constructions.

Arithmetic and the Least Number Principle

Hilbert was not content with abstract logic alone. He imagined epsilon terms that select the least number satisfying a property.

This adds a computational flavor: εxA(x) is now the first number meeting A, if one exists.

This idea leads to deep subtleties. Nested epsilon terms create dependencies: changing one choice can ripple through a proof, requiring backtracking.

This mirrors the challenges faced in early algorithms and in modern computational logic.

Ackermann formalized these procedures in the 1920s, developing the epsilon substitution method, which iteratively replaced epsilon terms with concrete numbers to verify consistency.

But Hilbert’s methods ran into limitations with second-order arithmetic.

Gödel’s incompleteness theorems would later show that no finitely verifiable system can capture all truths of arithmetic.

Still, the epsilon calculus remains a window into the interplay between choice, existence, and computation.

Epsilon in Linguistics and Philosophy

Surprisingly, epsilon terms leap beyond mathematics. In linguistics, they model indefinite pronouns and anaphora. Consider:

“Every farmer who owns a donkey beats it.”

Formalizing this in logic is tricky: which donkey does “it” refer to? Linguists like von Heusinger use epsilon terms as choice functions, tracking referents contextually.

Here, Hilbert’s ghosts help untangle ambiguity in natural language.

Philosophically, epsilon terms probe the concept of arbitrary objects. εx(¬A(x)) represents an object where A holds if and only if it is universal.

These placeholders reveal a subtle point: reasoning about existence doesn’t always require committing to a specific instance.

Epsilon terms formalize existence without commitment, an idea that resonates in metaphysics, epistemology, and even computer science.

Today, epsilon terms underpin techniques in automated theorem proving. Systems like Isabelle or HOL employ variants of the epsilon operator to reason symbolically, echoing Hilbert’s vision.

Bourbaki flirted with epsilon notation in their formal set theory. And in computational linguistics, epsilon-like constructs handle reference, choice, and ambiguity in natural language processing.

The broader lesson is striking: a simple idea (a term that picks “some x” satisfying a property) reappears in multiple domains.

Whether in logic, computation, or language, Hilbert’s ghost shows us that existence can be represented, reasoned with, and manipulated, without ever needing a concrete instantiation.

Some Closing Reflections

In the end, the epsilon calculus is more than a technical device tucked away in the machinery of proof theory.

It is a meditation on choice, existence, and reasoning itself.

It exposes something subtle about mathematical thought: that much of our reasoning depends not on concrete objects, but on the disciplined handling of absence, uncertainty, and potentiality.

Hilbert’s ghosts teach us that placeholders are not weaknesses in our reasoning, but sources of power.

They act as guides through proofs, scaffolding our arguments while remaining themselves unseen, and then quietly disappearing once their work is done.

In this sense, epsilon terms mirror how we think more generally: we operate with provisional assumptions, hypothetical entities, and abstract stand-ins, trusting that clarity will emerge downstream.

To follow an epsilon term is to follow the logic of existence itself: subtle, elusive, and yet profoundly generative.

And perhaps, in a larger sense, this story is not just about logic or mathematics at all. It is about how humans navigate uncertainty.

The world itself is filled with “some x”: unknown causes, unseen mechanisms, future possibilities, and half-formed explanations.

We reason about them, build models around them, act as if they exist, and often only later discover what they truly were, if we ever do.

Hilbert’s epsilon calculus gives formal expression to this deeper pattern of thought: the art of working productively with what is not yet concrete, of building knowledge on placeholders, ghosts, and promises of existence.

In that sense, the epsilon operator is not just a symbol in logic, but a quiet metaphor for how understanding itself moves forward.